- Professor of political science and Founding Director of the Centre on Governance of China and the World at the University of Hong Kong

- Former Director of Research and Senior Fellow of the John. L. Thornton China Center at The Brookings Institution

- An expert in China’s political science and China-US relations

- A Director of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations

- Professor of political science and Founding Director of the Centre on Governance of China and the World at the University of Hong Kong

- Former Director of Research and Senior Fellow of the John. L. Thornton China Center at The Brookings Institution

- An expert in China’s political science and China-US relations

- A Director of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations

Cheng Li serves as professor of political science and founding director of the Centre on Governance of China and the World at the University of Hong Kong. He served as director of the John L. Thornton China Center (2014-2023) and a senior fellow in the Foreign Policy program at Brookings (2006-2023). He is also a director of the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations. Li focuses on the transformation of political leaders, generational change, the Chinese middle class, and technological development in China.

Li grew up in Shanghai during the Cultural Revolution. In 1985, he came to the United States, where he received a master’s in Asian studies from the University of California, Berkeley and a doctorate in political science from Princeton University. From 1993 to 1995, he worked in China as a fellow sponsored by the Institute of Current World Affairs in the U.S., observing grassroots changes in his native country. Based on this experience, he published a nationally acclaimed book, “Rediscovering China: Dynamics and Dilemmas of Reform” (1997).

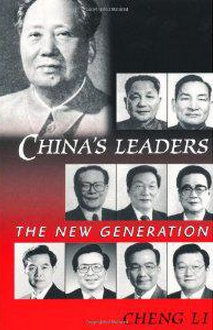

Li is also the author or the editor of numerous books, including “China’s Leaders: The New Generation” (2001), “Bridging Minds Across the Pacific: The Sino-U.S. Educational Exchange 1978-2003” (2005), “China’s Changing Political Landscape: Prospects for Democracy” (2008), “China’s Emerging Middle Class: Beyond Economic Transformation” (2010), “The Road to Zhongnanhai: High-Level Leadership Groups on the Eve of the 18th Party Congress” (in Chinese, 2012), “The Political Mapping of China’s Tobacco Industry and Anti-Smoking Campaign” (2012), “China’s Political Development: Chinese and American Perspectives” (2014), “Chinese Politics in the Xi Jinping Era: Reassessing Collective Leadership” (2016), “The Power of Ideas: The Rising Influence of Thinkers and Think Tanks in China” (2017), and “Middle Class Shanghai: Reshaping U.S.-China Engagement” (2021). He is currently completing a book manuscript with the working title “Xi Jinping’s Protégés: Rising Elite Groups in the Chinese Leadership”. He is the principal editor of the Thornton Center Chinese Thinkers Series published by the Brookings Institution Press.

Li has advised a wide range of U.S. government, education, research, business, and not-for-profit organizations on work in China. Li is also a distinguished fellow of the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy at University of Toronto, a nonresident affiliated fellow at the Paul Tsai China Center at Yale University, a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, a member of the Institute of Current World Affairs, and a member of the Committee of 100. Before joining Brookings in 2006, he was the William R. Kenan professor of government at Hamilton College, where he had taught since 1991.

Li has been a recipient of fellowships or research grants from the Smith Richardson Foundation, the Freeman Foundation, the Peter Lewis Foundation, the Crane-Rogers Foundation, the Emerson Foundation, the United States Institute of Peace, Hong Kong Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences and the Chiang Ching-Kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange. From 2002 to 2003, he was a residential fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

He is frequently called on to share his unique perspective and insights as an expert on China. He has appeared on CNN, C-SPAN, CGTN, BBC, ABC World News with Diane Sawyer, PBS NewsHour, CNN International’s Christiane Amanpour, Foreign Exchange with Fareed Zakaria and NPR’s Diane Rehm Show. He has been featured in The New York Times, The Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, Time magazine, The Economist, Newsweek, Business Week, Foreign Affairs, Foreign Policy magazine and numerous other publications. Li previously served as a columnist for the Stanford University journal China Leadership Monitor. He is a regular speaker and participant at the Bilderberg Conference